Third in a series

Ethane’s sweet trek from Houston to Vietnam and back

Byproduct of Texas shale gas turns region into world supplier of plastics

By Jordan Blum STAFF WRITER

Open a bag of frozen shrimp from Walmart. Toss the packaging in the trash.

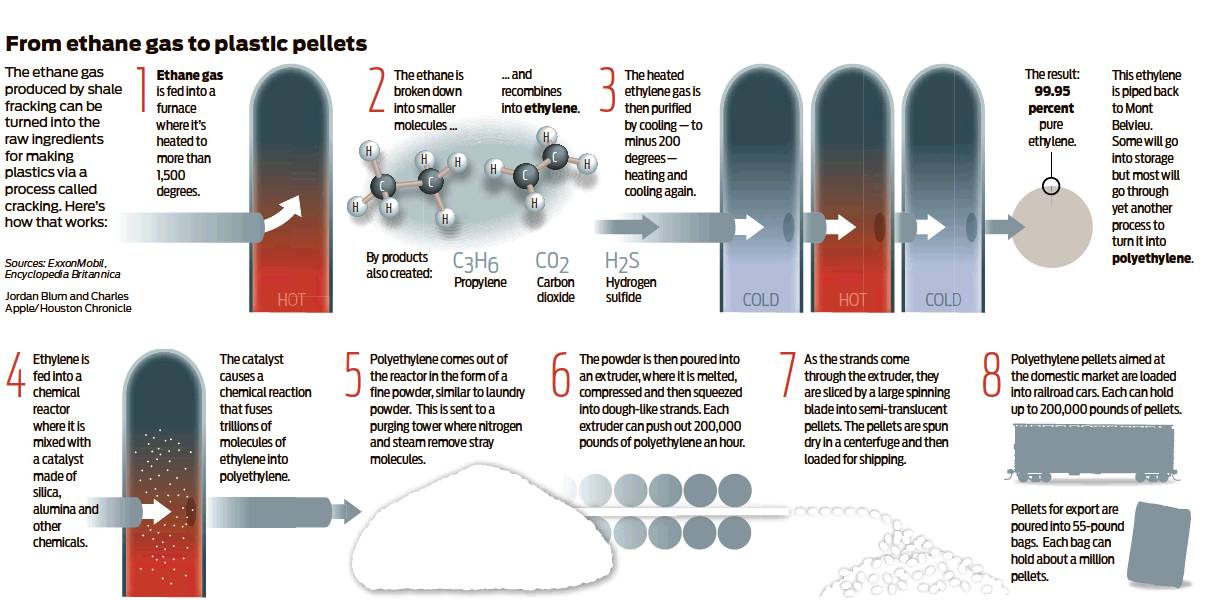

Two routine tasks, but they represent final commercial destinations for ethane molecules freed from Texas shale, a journey that has taken them not only hundreds of miles to Houston’s massive petrochemical complex, but also around the world and back again in the carefully choreographed dance of global supply chains.

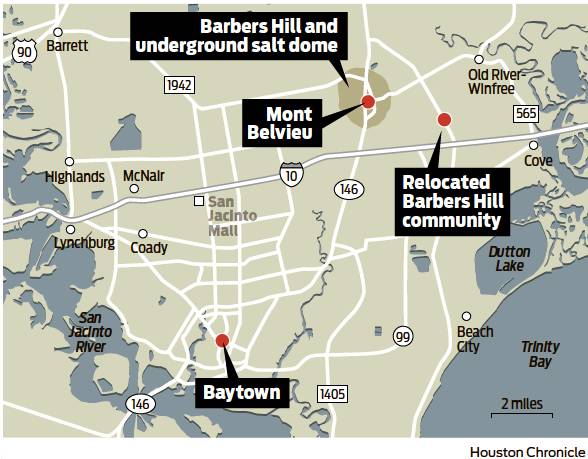

Each day, hundreds of trucks and rail cars move pellets of ethane-derived polyethylene from petrochemical plants, such as Exxon Mobil’s in Mont Belvieu, to the Port of Houston. There, the pellets are loaded by the ton onto container ships and bound for ports like Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam, where the molecules of hydrogen and carbon will be transformed yet again — into plastic wrap, trash bags and packaging for farm-raised shrimp found in freezer sections of grocery stores in Houston and across the country.

Ultimately, the shipments of polyethylene, the world’s most common plastic, will bring billions of dollars into the Houston economy and generate jobs for factory workers, longshore workers and truck drivers. Patrick Jankowski, chief economist at the Greater Houston Partnership, estimates the growth in U.S. plastics exports — dominated by the Gulf Coast and expected to double by 2030 — will have created some 10,000 local jobs in the region by early next decade.

“Nobody could have ever foreseen the U.S. becoming a major exporter of plastics,” said Neil Chapman, a senior vice president at Exxon Mobil. “It’s a byproduct of shale gas. That’s what’s truly amazing about this breakthrough.”

Industrial orchestra

Roughly three-fourths of the nation’s waterborne polyethylene exports leave from the Port of Houston, which is expected to move some 7 billion pounds of the plastic this year, up 35 percent from 2017. Each day, hundreds of 40-foot containers filled with plastics resins, primarily polyethylene pellets, are shipped from the port.

The container terminal seems a cacophony of noises — roaring trucks, whirring cranes and clanking containers. But each piece of equipment has specific notes to play in an industrial symphony that requires precision.

The newest cranes, which reach nearly 300 feet into the sky and cost $11 million each, can load an average of 35 containers an hour, reaching across ships that are 22 containers or nearly 180 feet wide. Four cranes can load a ship, which typically carries about 2,500 containers, in about 18 hours.

Louis Alberti, a crane operator for the past 15 years, routinely lifts two 20-foot containers at a time in a maneuver called “twin picking.” He swings them up and over stacks of containers on the ship and tucks them into tight, secure positions, where they’ll stay for the weekslong ocean crossing.

Alberti, 48, is among the workers benefiting from the boom in plastic exports, which has led to more hiring, more overtime, and extended hours at the port, which now operates until 11 p.m. Alberti’s 22-year-old son, Jimmy, recently got a longshore job at the port, while Alberti, a third-generation longshore worker, is racking up overtime.

With new night shifts that pay time-and-a-half, Alberti said he has doubled his annual earnings from roughly $100,000 to $200,000 by working 60 to 80 hours a week.

“It’s hard, but you have to work through it,” said Alberti, 48. “I can’t imagine having a 9-to-5 job. I’d probably be bored.”

Polyethylene accounts for about 15 percent of the cargo leaving the Port of Houston’s Bayport container terminal. After the ships are loaded, they will navigate what has become the nation’s busiest ship channel. Vessels routinely squeeze through the narrow waterway by aiming directly at an oncoming ship before getting pushed safely aside by the water pressure generated by the wakes. The pilots call it “Texas chicken.”

Within a few hours, the ships will reach the Gulf of Mexico, beginning a two- to three-week journey that will take them through the Panama Canal into the Pacific Ocean and on to Asia.

Next stop: Singapore

The Port of Singapore is the world’s biggest transshipment port — an intermediate stop where cargoes are unloaded, then reloaded onto the other ships that will take the containers to their ultimate destinations.

This is where Alex Dam makes his polyethylene connection.

Dam is executive vice president of Thanh Phu Plastic Packaging, a Vietnamese company that makes packaging for brands such as the Chicken of the Sea, a unit of Thai Union International, and Huggies disposable diapers, made by Irving-based company Kimberly-Clark.

Just a few years ago, Dam said, his company was buying polyethylene pellets, also called resins, from Middle Eastern and Asian chemical-makers, which sold them more cheaply than U.S. companies. Then came the flood of ethane.

“The shale gas is changing a lot of the trend,” Dam said.

Exxon Mobil sells a premium resin to Thanh Phu Plastic Packaging, which typically orders 10 containers, or 250 tons, of polyethylene pellets at a time, shipped from Singapore to the port in Ho Chi Minh City. Dam’s plant is located about 15 miles from the port, in the southwestern part of the city.

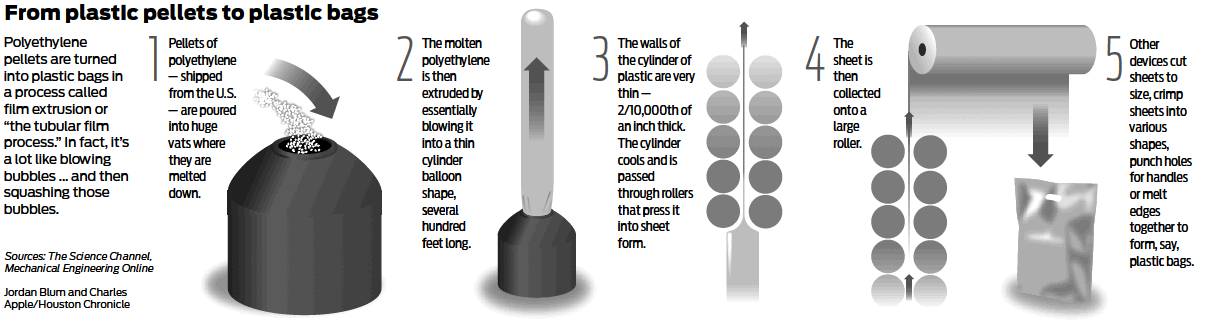

The plant’s operations are run primarily by computers, which control a process known as “blown film” to turn polyethylene pellets into flexible plastic packaging. The tiny pellets are fed by the thousands into a hopper, then funneled into a heated tube, where they are melted, compressed, formed into circles and inflated into spheres, much like glass blowing.

“We make it like a bubble,” Dam explained.

Rising middle class

The automated process forms the bubbles into different shapes and thicknesses by adding thin layers of polyethylene — so thin they are invisible to the human eye. The blown plastic is then cooled and run through rollers that flatten them into rows of film.

The number of layers in the packaging depends on the products they will protect. Plastic bags that hold seafood, for instance, are thicker and stronger so they won’t crack when frozen. Diaper packaging is thinner, more flexible and soft to the touch.

About 500 people work in the plant, about the same as 10 years ago. The critical difference is many of the jobs have shifted from assembly-line work to skilled positions requiring technical abilities, computer literacy and higher levels of education. Today, 1 in 5 of the plant’s employees are engineers, part of arising middle class that is fueling a rapidly growing consumer economy in Asia.

The global middle class is forecast to more than double from 2 billion people in 2010 to more than 5 billion by 2030, with Asia accounting for 90 percent of the increase, according to the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank. As middle classes grow in places like Vietnam, China and India, the demand for electronics, cars, food and other consumer products, all with components or packaging made of plastic, is expected to follow.

Global polyethylene demand is growing about 4 percent a year, projected to hit 100 million metric tons — more than five times North American consumption — in 2018 and 120 million tons by 2023.

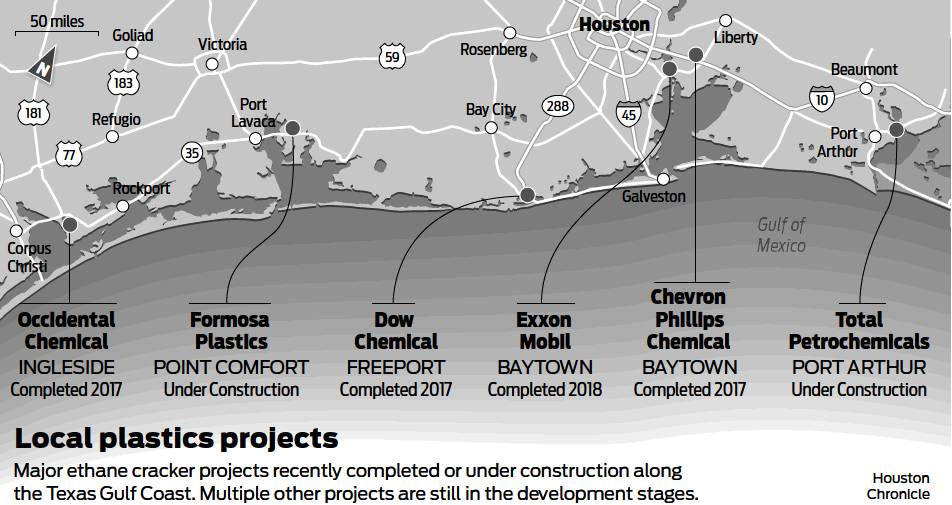

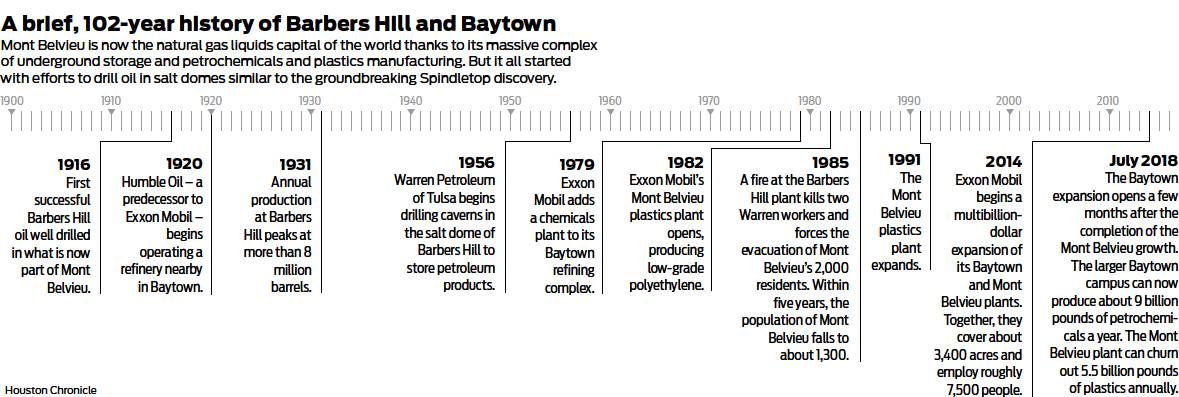

That trend is driving the billions of dollars in petrochemical investment along the Gulf Coast, with nearly all of it targeting foreign markets. For example, all of the polyethylene produced from Exxon Mobil’s $6 billion expansion in Mont Belvieu and Baytown is headed overseas.

“This is areally dynamic market,” said Cindy Shulman, Exxon Mobil’s vice president of plastics and resins. “It’s growing because global living standards around the world continue to improve, and that’s a great thing.”

Price of progress

All this progress has not come without costs, some dear, to the environment. Fears are growing that the world is drowning in plastics; measured by weight, there could be more plastic in the ocean than fish by 2050, according to the Plastic Pollution Coalition, an environmental advocacy group.

About one-third of all plastics are used once and thrown away. Of the world’s roughly 6.5 billion metric tons of plastic waste, only 9 percent was recycled and 12 percent incinerated. The rest is sitting in landfills, oceans or other parts of the environment, where it will take more than 400 years for much of it to degrade.

If production and waste management trends continue, 12 billion metric tons of plastic waste — equivalent to the weight of 35,000 Empire State buildings — will be in landfills or the environment by midcentury, according to a study by the University of California at Santa Barbara and the University of Georgia. At least 8 million tons of plastic end up in the world’s oceans each year.

Neil Carman, clean air director of the Lone Star Chapter of the national advocacy group Sierra Club, said he worries more about the impact of drilling, fracking and petrochemical processes. Exxon Mobil’s Baytown complex, for example, has a history of exceeding air pollution limits, which last year led to a federal court to impose $20 million in penalties on Exxon Mobil. The company is appealing.

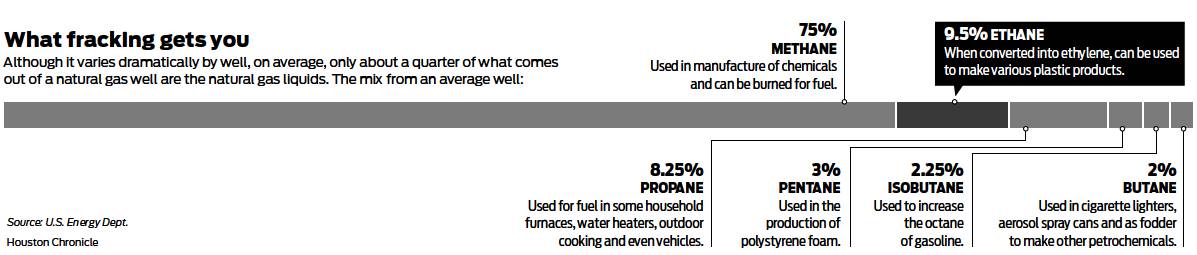

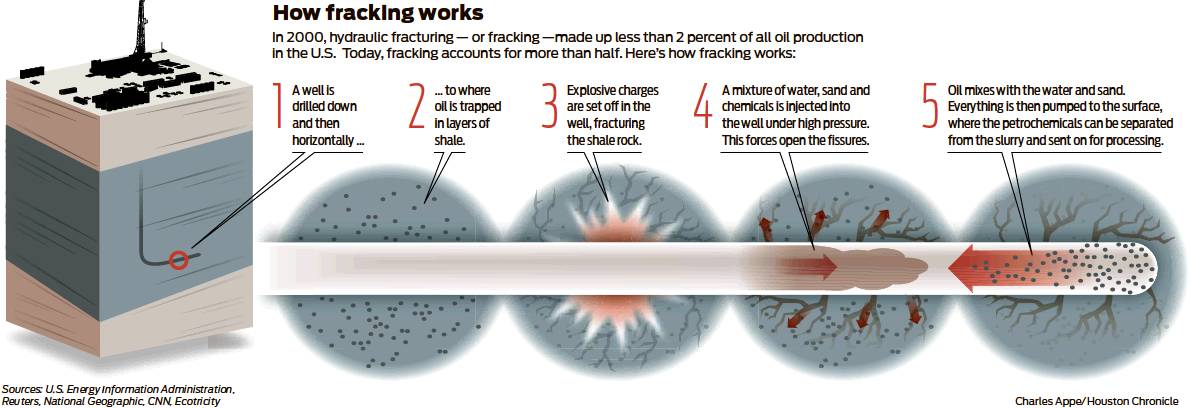

At well sites, emissions from diesel engines that power fracking foul the air while disposal wells used to hold spent fracking water have been linked to an increase in earthquakes. The main component of natural gas, methane, is a powerful greenhouse gas that escapes during drilling and production, contributing to climate change.

“We’re still in the process of uncovering these enormous public health and environmental effects,” Carman said. “We’re not doing enough to assess these impacts and address them.”

Industry responds

Exxon Mobil and other petrochemical-makers are researching ways to increase the amount of recycled materials in their products while developing thinner, lighter plastics that use less material while maintaining their strength and flexibility.

Shulman said the thinner and stronger plastics allow companies to use 40 percent less packaging. That means less plastic is required for each product, reducing the amount that gets thrown out.

“It costs less to ship these products. They take up less room on the shelves,” she said. “They keep food fresh longer.”

Chicken of Sea’s frozen shrimp, protected in the packaging made in Vietnam, will end up on freezer shelves in stores such as Walmart, Target and Kroger, and ultimately on the plates of consumers in Houston and around the country. As families tuck into gumbos or seafood stews, they probably won’t give a second thought to packaging that brought the shrimp from farm to table, or the trash bag where the packaging will end up.

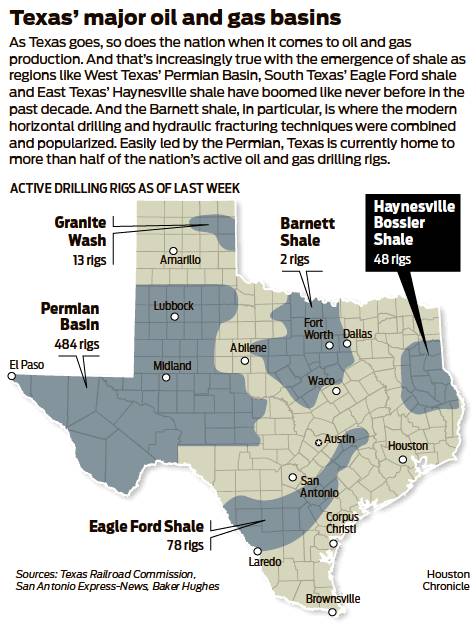

They are merely conveniences of modern life, conveniences made possible by a natural gas well called Eagles in East Texas and thousands of others like it in shale fields across America. [email protected] twitter.com/jdblum23