Sometimes there may be terminal hematuria, sexual dysfunction and abnormal weight loss are other side effects of the medicine. Carminative herbs stimulate the digestive system to deliver the right ingredients to the penis. To keep the sexual life alive both partners must make efforts. Reckless sale of medicines and medical drugs Puts consumers at risk.

Second in a series

In petrochemical boom, ‘all roads lead to Baytown’

Natural gas liquids from shale fields processed, transformed into plastics

By Jordan Blum STAFF WRITER

MONT BELVIEU — They say geography is destiny, but in this small city east of Houston, the force shaping its history, economy and future is geology.

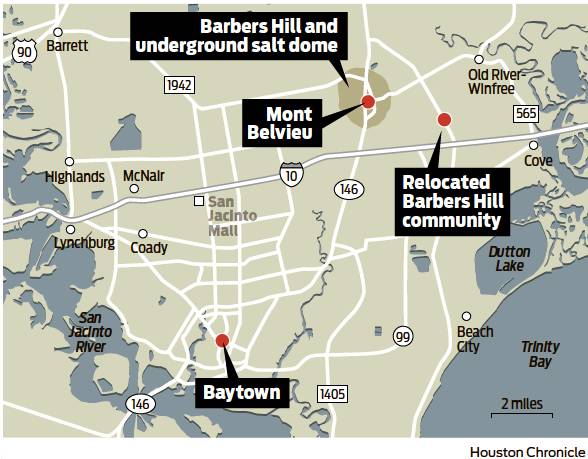

Mont Belvieu is built atop a salt dome formed more than 100 million years ago from deposits likely left by an ancient inland sea that cut across the North American continent. For more than 60 years, energy companies have used it as a natural storage tank, carving out salt caverns some 3,000 feet deep to hold millions of barrels of petroleum products.

Today, those caverns are increasingly filled with ethane and other natural gas liquids that feed the plastics and chemical industries, making Mont Belvieu and its neighbor to the south, Baytown, the focal point of the Gulf Coast petrochemical boom. Here, where rice fields once stretched as far as the eye could see, Exxon Mobil alone has invested some $6 billion to dramatically expand its 36-year-old plastics plant as well as its sprawling refining and chemicals complex in Bay-town.

At these plants, the ethane molecules that squeezed through fissures in shale rock, flowed up a Texas well and traveled more than 150 miles by pipeline will undergo chemical changes to transform them from once-overlooked byproducts of oil and gas drilling into one of most ubiquitous materials on earth. Hundreds of other pipelines stretching across Texas and beyond will carry millions more barrels of natural gas liquids from U.S. shale fields, converging near the salt dome under Mont Belvieu’s Barbers Hill.

“All roads lead to Texas,” said Kim Haas, Exxon Mobil’s operations manager, “and specifically the Bay-town area.”

Hydrogen meets carbon

Barbers Hill rises 85 feet above sea level, a mile-wide distortion in an otherwise flat landscape. First settled more than 175 years ago and named for an early rancher, Amos Barber, the area began attracting oilmen after another salt dome called Spindletop began gushing crude in 1901.

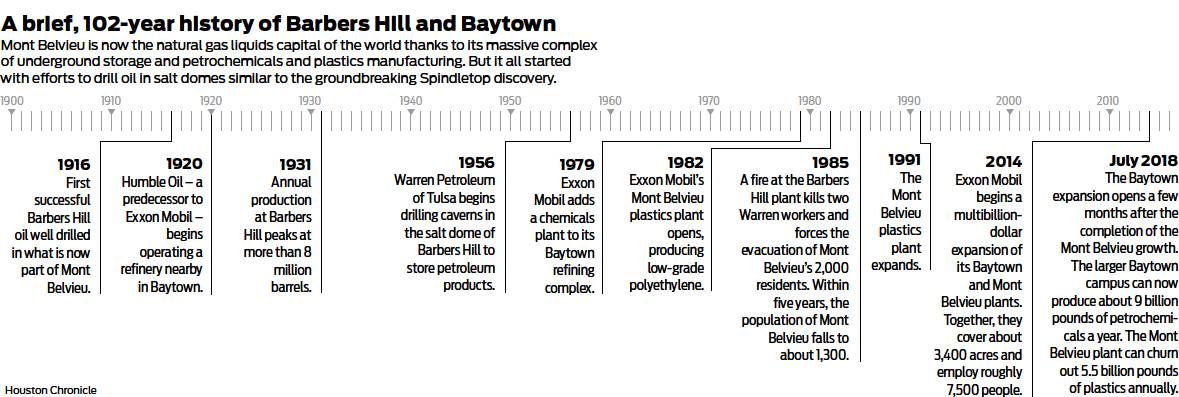

The first successful Barbers Hill oil well was drilled in 1916, and annual production peaked at more than 8 million barrels in 1931. About 25 years later, Barbers Hill got asecond life when Warren Petroleum, a Tulsa company now part of Chevron, starting drilling caverns to store petroleum products.

The community, however, was jolted in 1985 by fires on Barbers Hill that killed two Warren workers, forced the evacuation of Mont Belvieu’s 2,000 residents, and led the city to distribute letters to newcomers warning of the “serious danger and possible death” that came with living there. The population fell to about 1,300 by 1990.

But with improved safety, the recent petrochemical boom has revived the community, whose population has more than doubled since 2000 to about 6,000 residents. Today, Barbers Hill sits atop roughly 150 caverns potentially holding some 300 million barrels of petroleum products.

This is the next stop for the natural gas liquids produced by Exxon’s subsidiary XTO Energy. Here, processing plants known as fractionators use varying pressures and temperatures to break the natural gas liquids into components, each with a slightly different combination of carbon and hydrogen, including butane (C4H10), propane (C3H8), pentane (C5H12) and, of course, ethane (C2H6).

The ethane is piped 10 miles to Exxon Mobil’s Bay-town complex, which is simultaneously one of the nation’s oldest and most modern plants. The refinery was built nearly a century ago by one of Exxon Mobil’s predecessor companies, Humble Oil. A chemical plant was added in 1979 and expanded in 1997.

Four year ago, Exxon Mobil launched another Baytown expansion, which, with the associated expansion of the sister plant in Mont Belvieu, is the company’s biggest U.S. industrial investment since Exxon and Mobil merged 20 years ago. The projects vastly increase Exxon Mobil’s capacity to process ethane into ethylene, the basic chemical building block of most plastics, and then into the most common plastic, polyethylene.

At the peak of construction, nearly 6,000 people worked at the two sites. The expanded Baytown facility, which began operations in late July, can produce about 9 billion pounds of petrochemicals a year, including 3.3 billion additional pounds of ethylene.

The focus of the Baytown expansion was eight furnaces, each costing more than $100 million and standing 23 stories tall — nearly the height of NRG Stadium . The furnaces, built in Thailand, are the heart of aplant known as a cracker, which gets its name from the process that uses extreme heat to crack ethane molecules in half and trigger chemical reactions that form ethylene.

Kevin Campbell keeps track of much of the process in his job as a hot ends coordinator, monitoring the operations and safety of the furnaces — the “hot end” of the cracking process. These control room jobs can easily pay $70,000 a year.

Exxon Mobil runs four overlapping 12-hour shifts, the first beginning at 4 a.m. Campbell, who works an early shift, sits in acontrol room, darkened to make it easier to see his console, where he’s observing digital images and the constant flow of data to track furnace operations.

He and his colleagues compare the job to flying an airplane, mostly uneventful, but requiring strict oversight and cool, rapid decision-making when needed.

“Right now it’s calm,” Campbell said. “But it’s not boring. It’s very exciting.”

99.9 percent pure

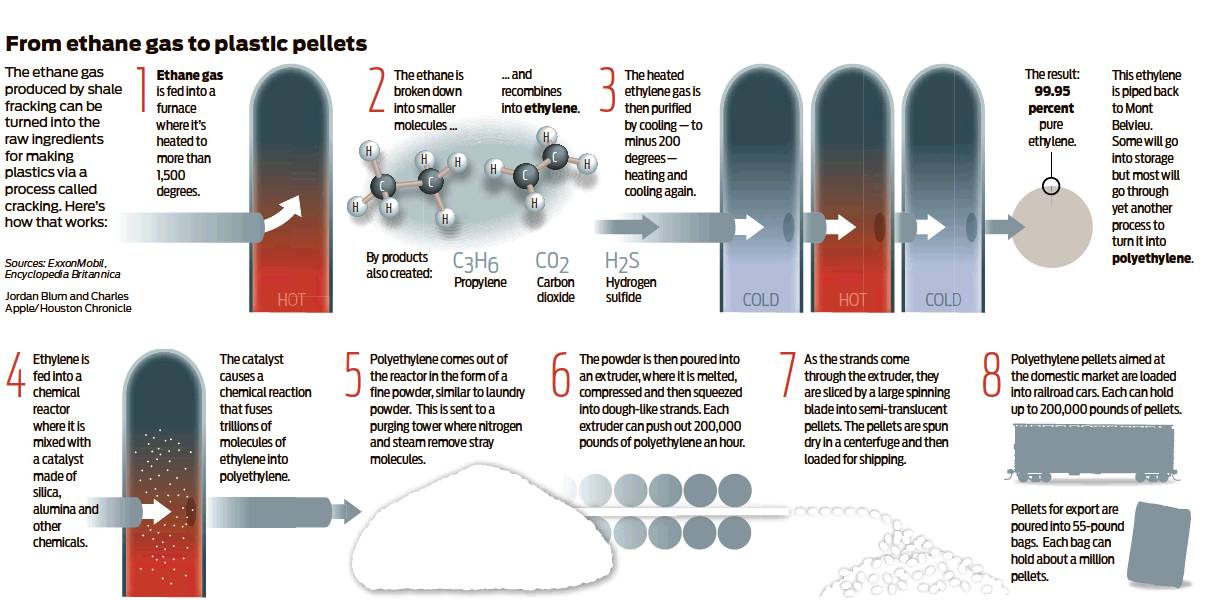

The ethane enters the Baytown plant as a gas, fed by pipeline into a furnace, where it’s injected with steam and heated to more than 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit — hot enough to melt gold and silver.

In less than a half-second, the process breaks the ethane molecules, which contain two carbon and six hydrogen atoms, into two radicals each containing one atom of carbon and three of hydrogen. That frees the carbon and hydrogen atoms to recombine, forming ethylene, made of two atoms of carbon and four of hydrogen (C2H4), as well as byproducts such as propylene (C3H6), carbon dioxide (CO2) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S).

The heated gas then moves through a series of towers, where it is cooled, reheated, pressurized and cooled again — to minus-200 degrees — to remove byproducts and impurities. Finally, the ethylene is funneled through a 355-foot tower known as a splitter, where any remaining ethane is removed and recycled.

The result: 99.95 percent pure ethylene.

The ethylene is piped back to Mont Belvieu, where some will be stored in the salt caverns, but most will feed another process that will change the hydrocarbons liberated from Texas shale once again.

Where the Baytown complex used heat and pressure to crack ethane into ethylene, Exxon Mobil’s Mont Belvieu plant relies on chemical reactions to fuse trillions of ethylene molecules into polyethylene.

The process begins in a chemical reactor, a tall cylindrical tower that’s fed ethylene by pipelines at least 10 inches in diameter. The reactor operates like a blender, mixing ethylene with a catalyst made from silica, alumina and proprietary materials that Exxon Mobil won’t disclose.

The catalyst, a fine powder that feels like dust, sparks a chemical reaction that fuses the ethylene molecules together. By mixing different catalysts from specific materials, manufacturers can produce different grades of plastic with varying levels of strength and flexibility.

The Mont Belvieu plant opened in 1982, producing mainly low-grade, flexible polyethylene used in plastic wrap and food packaging, and expanded nine years later to produce plastic for more rigid products, such as milk bottles. The most recent expansion, completed late last year, is dedicated to high-performance polyethylene that is light, flexible and strong.

Paul Fritsch is the plant manager. Achemical engineer by training, he has worked with Exxon for nearly three decades, overseeing expansions as far away as Singapore. He can touch almost any plastic in a supermarket and identify the type of polyethylene.

“When I go grocery shopping,” he said, “I pick up the packaging and look to see if it’s one of our customers.”

Made in America

Polyethylene comes out of the chemical reactors as a powder, similar to laundry detergent. It’s fed into a purging tower where nitrogen and steam remove any residual ethylene and hydrocarbons that didn’t properly bond.

The powder is then transported to hoppers that funnel the material to an extruder, which melts the plastic, compresses it and pushes out dough-like strands of polyethylene, much like a pasta maker. Each extruder can churn out 200,000 pounds of polyethylene an hour.

As the strands come through the extruder, they are sliced by a large spinning blade into semi-translucent pellets. The pellets go into a centrifuge, where they are cooled by water, then spun dry, much as a salad spinner pulls moisture from lettuce leaves.

After quality testing, the plastic is loaded into as many as 35 rail-cars, each holding about 200,000 pounds of polyethylene pellets, and shipped throughout the country to customers who shape the polyethylene pellets into finished plastics products. About 40 percent of the polyethylene is made for the domestic market.

Polyethylene pellets marked for export are mechanically packaged in 55-pound bags, each holding about 1 million pellets. Every hour, the plant fills about 10,000 bags, which are loaded onto pallets, each holding 55 bags, and trucked to a 70-acre storage yard. As many as 100,000 pallets are kept for up to 45 days until they can be loaded into containers and shipped out of the Port of Houston.

“Our production is 24 hours a day,” Fritsch explained, “but the Port of Houston isn’t open 24-7.”

With the expansions completed, Exxon Mobil’s Mont Belvieu and Baytown campuses together cover about 3,400 acres, the equivalent of three Houston downtowns. The Mont Belvieu plant, which has doubled its polyethylene output to 5.5 billion pounds a year, is now the second-largest plastics plant in the world, after the Borogue complex in Abu Dhabi.

The Baytown and Mount Belvieu plants together employ 7,500 people, and Exxon Mobil estimates that the number doubles to 15,000 when counting contractors and jobs at local suppliers, restaurants and other businesses that support the plant. Exxon pays more than $150 million a year in local taxes and fees.

The plants also have contributed to a surge in exports that has made Houston one of few regions in the country that exports more than it imports. That brings new money into the area — tens of billions of dollars that can be used to expand business, hire workers and increase wealth.

“We’re going to have things that are made in America again and getting shipped overseas,” Fritsch said. “That’s what’s exciting about shale gas. It’s the explosion of industry again in the U.S.” [email protected] twitter.com/jdblum23